#910 Best of Juicebox: Emotions at Diagnosis & Diabetes Distress

Originally posted on Nov 16, 2020. Erica is a licensed marriage and family therapist who herself has had Type 1 diabetes for over 30 years and who specializes in working with people with diabetes and their families and caregivers—from those newly diagnosed to those experiencing it for decades. She and Scott discuss burnout, emotions surrounding diagnosis, and dealing with diabetes distress and constructive ways to prevent it from impairing one’s function.

You can always listen to the Juicebox Podcast here but the cool kids use: Apple Podcasts/iOS - Spotify - Amazon Music - Google Play/Android - iHeart Radio - Radio Public, Amazon Alexa or wherever they get audio.

+ Click for EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

DISCLAIMER: This text is the output of AI based transcribing from an audio recording. Although the transcription is largely accurate, in some cases it is incomplete or inaccurate due to inaudible passages or transcription errors and should not be treated as an authoritative record. Nothing that you read here constitutes advice medical or otherwise. Always consult with a healthcare professional before making changes to a healthcare plan.

Scott Benner 0:00

Hello friends, welcome to episode 910 of the Juicebox Podcast.

Today we're going to revisit episode 407 with the best of the Juicebox Podcast. Today's episode is from November 16 2020. And it was titled emotions at diagnosis and diabetes distress. This episode is myself and Erica Forsyth. Of course, Erica is a licensed Marriage and Family Therapist and she has had type one diabetes for over 30 years, you can check her out at Erica forsythe.com. While you're listening, please remember that nothing you hear on the Juicebox Podcast should be considered advice medical or otherwise, always consult a physician before making any changes to your health care plan are becoming bold with insulin. If you head to cozy earth.com You will save 35% off your entire order with the offer code juice box at checkout one word juice box at checkout at cozy earth.com to get 35% off everything they have joggers, sheets, towels, pajamas, they've got so much great stuff. Check them out cozy earth.com Use juice box at checkout to save 35%.

The podcast is sponsored today by better help better help is the world's largest therapy service and is 100% online. With better help, you can tap into a network of over 25,000 licensed and experienced therapists who can help you with a wide range of issues better help.com forward slash juicebox. To get started, you just answer a few questions about your needs and preferences in therapy. That way BetterHelp can match you with the right therapist from their network. And when you use my link, you'll save 10% On your first month of therapy. You can message your therapist at any time and schedule live sessions when it's convenient for you. Talk to them however you feel comfortable text chat phone or video call. If your therapist isn't the right fit for any reason at all. You can switch to a new therapist at no additional charge. And the best part for me is that with better help you get the same professionalism and quality you expect from in office therapy. But with a therapist who is custom picked for you, and you're gonna get more scheduling flexibility, and a more affordable price betterhelp.com forward slash juicebox that's better help h e l p.com. Forward slash juicebox save 10% On your first month of therapy.

Hello, everyone and welcome to episode 407 of the Juicebox Podcast. On today's show, Erica Forsyte this year she has a master's in social work, and she specializes in diabetes. She's going to tell you more about in a second. But for right now please remember that nothing you hear on the Juicebox Podcast should be considered advice medical or otherwise. Please Always consult a physician before making any changes to your health care plan or becoming bold with insulin.

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 3:33

Hi, my name is Erica Forsythe. I am a licensed Marriage and Family Therapist and type one for over 30 years.

Scott Benner 3:42

Okay, so I'm already that quickly. My I don't think I have ADHD but when you said that I was like oh, we should just talk about being married. That would be anything. I find out why is it so hard to be married? And why do people argue about oh, but nevermind that's not what we're gonna do.

This show is sponsored today by the glucagon that my daughter carries. G voc hypo Penn Find out more at G voc glucagon.com forward slash juicebox this episode is also sponsored by the Omni pod tubeless insulin pump and you can get a free no obligation demo of the on the pod sent directly to you today by going to my Omni pod.com forward slash juice box try it on where it and see what you think before you commit. Don't forget to check out touched by type one there at touched by type one.org It is my absolute favorite diabetes organization. Check them out. They're also on Instagram and Facebook. poached by type one.org When were you diagnosed?

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 5:04

I was diagnosed at age 12. In the summer at summer camp,

Scott Benner 5:09

summer camp, not the best memory or not a bad memory.

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 5:13

Um, it was a pretty traumatic memory and diagnosis story then everyone has their own diagnosis story. It was over kind of a span of a couple months. It was a three week long summer camp, and I was diagnosed the night, the last night of the three week summer camp.

Scott Benner 5:32

Oh, and then they shipped you home lifeless.

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 5:35

They, I don't remember this, but they put me I was in sixth grade. They put me in a ambulance and I was on my way to diabetic coma. ketoacidosis. And so then my parents met me at the ER at some point that night. I know it's all kind of a blur. Yeah.

Scott Benner 5:52

So you were there for three weeks? Do you think it's just happening to you the entirety of those three weeks?

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 5:58

You know, I think they I was played in a volleyball camp in the beginning of the summer. And you know, to do that I had to have a you know, check in a physical and also before going away for the summer camp. And definitely, I was experiencing symptoms, but like many families we did not know, to look for, you know, frequent thirst, frequent urination and extreme weight loss. They just thought I was growing and it was hot. And I was playing lots of volleyball. And then I went off to summer camp. And you know, there was a flu going through the camp and I fainted. So they thought it was that they thought it maybe was I was going through puberty. You know, definitely was experiencing extreme fatigue, which was really abnormal, because I was an athlete. So you know, when you're not really looking for type one, the symptoms aren't as obvious. But then when you look back, and you can check off, you know, all of those symptoms like oh, my gosh, we should have known.

Scott Benner 7:03

Yeah, I mean, I guess especially when you're under the care of corny 18 year old camp counselors to their probably just like she's got the flow. Get her in a bed?

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 7:11

Oh, yes, yes. And you know, it was interesting. Finally, it was the last day of camp and is in most camps, you know, everyone that they care, they're getting ready for the banquet. And so all the girls are running around in a room or cabin, and I'm kind of going in and out of consciousness. They're, they're good, they're pumping or getting dressed or getting their makeup on. And I guess Finally, my symptoms were made known to a male camp counselor who happened to have type one. And so I remember him coming into our room, which was, you know, a male, and the girls cabin was was, like, you know, scary or just not normal. And he took my blood sugar, and I read high and at the time, that was like, I think over 600. And so I think it was really kind of a saving grace that he heard my symptoms. He was there. He knew to take my blood sugar. And you know, the rest is history. Yeah. Well,

Scott Benner 8:05

that is lucky, honestly, for you. All right. Well, I've never been to camp but you just made it sound not very good.

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 8:14

Oh, I love the camp, you know. And I went, it took me a couple years, but I went back in high school to kind of redeem my experience, because it was a special. It's a special place. That's cool.

Scott Benner 8:23

That's good. Yeah. Well, okay, so how long ago was this?

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 8:27

This was 30 years ago.

Scott Benner 8:29

Wow. All right. I'm gonna do some quick math and say that was 1990.

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 8:34

That was that was the summer of 1990. That was good math.

Scott Benner 8:38

Thank you. I'm very impressed that my ability to subtract three to subtract three from two. No, it's a negative one and knock 10 years off the 2000. The way I came up with, it really is brilliant. I don't want to bore anybody with it, but very impressed with what I learned in seventh grade and was able to retain Okay, so you're on the show today. You were you were actually suggested to me by someone else. Am I right about that? Yes. Yeah. So tell me what you do professionally.

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 9:10

Professionally, I am as I said it in a marriage and family therapist, but I specialize in working with people with diabetes in their families, their caregivers, as we know it, you know, it takes a village and it affects not only the person with diabetes, but everyone around him or her and so I I love my job and I love that I get to walk alongside people, you know, from newly diagnosed to you know, people living with it for 1015 2030 plus years who are maybe experiencing some, you know, distress or burnout or other issues that may or may not be really related to diabetes, but oftentimes, it can go back to that.

Scott Benner 9:59

Why don't we start with by burning out. And I'd love to know. So I'm assuming you see people who've been with diabetes for all length of time. And then how did you think of burnout? Like beyond, you know, just the word that gets kind of thrown around and in, you know, in social circles online, like what, what is burnout to you?

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 10:19

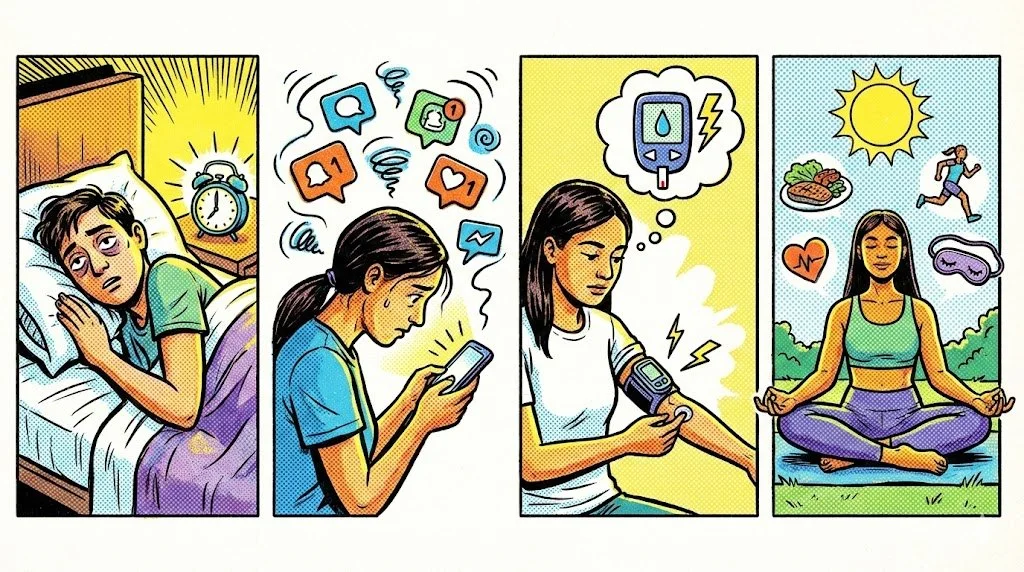

Yeah, so I, I think a lot of people really work on clarifying that diabetes, distress leads to burnout. And I think, you know, if you're experiencing distress over and maybe it comes and goes, but when you're actually experiencing burnout, people will describe it as you know, hitting a wall or maybe it's you feel like you just don't have the capacity to take care of yourself, manage your, your diabetes, maybe you want to skip a dose, maybe you just want to eat whatever and not think about, you know, carb counting or or think about, what where's my blood sugar now, what am I doing and all the things that we have to think about when we're about to do something or eat something or exercise. And so burnout is, I just want to think about it, I'm, I'm done, I want to take a break, and you might you probably not even doing that consciously. And I think, you know, burnout can be become very risky and scary when you're experiencing that over a prolonged period of time.

Scott Benner 11:27

Well, so you're saying that there's, like stressors that lead to the give up, like the hand throwing up, or even the subconscious hand throwing up of just like, I'm gonna get a bag of potato chips and sit on the sofa. Now, and this is the extent of my nutrition, like, I've just given up on everything, for reasons that can be external, and unseen. Is that possible, like so the way I to give you a little look into my head, that one of the reasons I make this podcast is because that I think that managing type one, diabetes is arduous, and that if you're mired down constantly in the math, and the worry, and things are always going wrong, and your meal spike, and you're high all the time, and you don't know why and then you drop low, and you're, you're concerned about being low, and then you over treat, you bounce up, this is an untenable way to live. And so I'm a big proponent of learning quickly how to manage the insulin so that you don't sort of start this journey of, of wherever, you know, it leads to that ends up with many people just being like, I can't do this, or this thing beats me all the time, or it's unknowable, or whatever, it ends up feeling like the different people. So it can be simple, right? Like, it could be like, one day, I just don't feel like giving myself a shot. And the next day, I don't know how many carbs are in this, and then it gets high. And I'll just leave it high and see if it comes down. And then these things build and build and build on themselves. Is that true?

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 12:59

Yes, I would say that, that is an accurate description, in addition to maybe other external kind of stressors or you know, feeling like you're, you're powerless. Or maybe you have a constant fear of, of having hypoglycemia, or you're really, you know, particularly in the teenage years, this is can be quite normal of feeling like you want to hide your diabetes from other people. or feeling like your doctor just doesn't understand what it's like. So these are, that those are maybe at play. And that addition to you know what, I just don't want to, I don't want to have to think about my blood sugar. And I want to eat five donuts this morning. And that can all snowball. Yes, yeah.

Scott Benner 13:45

And then before you know it, you're so mired down in it that you don't know how you got there. And there's no way to know how to get out anymore.

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 13:53

Right? And, and kind of, you know, when you're sick all the time, you kind of just get used to feeling sick, and then maybe one day, you're not sick, you're like, oh my gosh, I didn't know how good that feels to not be sick. I think you can become kind of used to maybe not feeling well, because of your sugar's are so high and then emotionally and mentally you're you're down and out. And you that just becomes your new normal, right. Your pain, pain, the knots, you know where I want to enter it? Yes,

Scott Benner 14:22

pain, pain starts that way. It's I had a motorcycle accident. I was like, 20. I don't have any, like health insurance. So when I was lucky enough to stand up, they were like, you're going to the hospital and I was like, I don't have insurance. You're not taking me to the hospital. I'm poor. I know where that leads to. So I just went home and my shoulder healed naturally, which obviously, in hindsight, wasn't a great decision. And over the next, you know, 20 years, it actually worked fine. But it turned out that you know, the weird healing process besides the lump that's on my shoulder that you can feel that doesn't belong there. It turned out that there was You know a calcification, they kept building and building and building a one day impinged a. My, my gosh, it's such a simple concept. Everybody gets their shoulder repaired that thing in their shoulder is called anybody, their rotator. Thank you, Erica impinged the rotator cuff, and it just snapped. Right but it happened super slowly and it hurt a little you got used to it hurt a little more you got used to it couldn't lift your arm up as high you got used to it. It's amazing how adaptive we can be, you know, and then I'll never forget the biggest relief I had in four years because it took 20 years for me to start noticing the problem and for years for it to explode. But I was trying to have a catch with my son one day thinking I was pushing through this, you know, stiffness as well how I imagined it my addled mind, you know. And then suddenly, I said to him, like, oh my god, I worked through it, it's, it feels great. And for the next 20 minutes, it was perfect, until I realized that my rotator cuff, it's the tendonitis. Right, and just the snapping of it alleviated my pain for a while until a new pain showed up. I think that's exactly what you're talking about is that it? You know, you start off with a you know, not having diabetes, your blood sugar's in the 80s all the time, then suddenly, it's not anymore. Now, you know, you're in the 90s the hundreds you're honeymooning, and then suddenly, it's 120 and 130. And when 15 Before you know it, you feel completely normal at 200. And you're not, you just don't realize it. So

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 16:31

yes, no, that's, that's a great analogy. And I'm sorry, that happened

Scott Benner 16:35

that please, what am I gonna do? You know, the day I figured it out, I couldn't hold a water bottle in my right hand, oh my god, like, I'm gonna move this to my left hand and call a doctor. But, please, smart move would have been when I was 20 years old, going a little bit in debt and having my shoulder. But I was really broke back then Eric, and anything over $45 seemed like a million. So I Oh, yes. Luck, you know. But But so what are people? Given that you don't see it happening to you? I mean, that's why my argument is, you know, just stop it from happening, you know, and but you know, shy of that being able to be your reality. So you don't find a podcast that helps you manage your insulin? How do I like, what are my signs if I because I'm assuming I'm, I'm hoping that a loved one sees this. Right?

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 17:28

Right. Yes. I mean, I know, you know, I speak a lot from you know, the, the person who's living with diabetes can experience the, you know, distress and burnout. But obviously, the caregiver, like yourself can too, because it's, it's constant. I think some of you know, the, the obvious signs would be, you know, not doing some of the things that you used to do, like, for example, maybe your check, it used to check frequently, and then now it's becoming less frequent. Or you're just maybe looking for signs that something might not be something is bothering you that you might not be feeling as, as hopeful in, in life in general, but also with, with your diabetes care, you might be experiencing, you know, this is what a lot of younger, my younger clients will talk about, or experience, just the guilt and shame around the number. Because there is such a hyper focus on the numbers. You know, when I was first diagnosed, I went to a large Children's Hospital, and whenever I, they would take your a one C, right there, it would just like from a finger stick, and then it would it would compute, and then they would apply your a one C to a letter grade. Oh, so this is this is in the night, you know, the 90s, early 90s. And so if you were in the right zone, it was an A, if you were you know, eight to 10, you are a B or in higher. I mean, there were times where I remember I had like a D. And so talk about, you know, they're trying to encourage you to have a better grade. But that certainly started the turn of the course for me and having some shame based thinking around my numbers. And I hear a lot of clients talk about you know, I don't want to check because I know it's gonna be 350 So of course you don't then you you're connecting that number to who you are as a person, how you're doing with your diabetes management. And so of course you don't want to check it. Or look at your CGM.

Scott Benner 19:36

I'm fixing metal spirals who the moron is that thought that that was would have been the way to go you know, you don't will do will grade them and the people are doing poorly will give them really bad grades that should motivate them. i Who thinks that way but not like at least they could have rated you on like the popularity of Nirvana songs like you know, like if you you had like an 85 You were like teen spirit but You know, if you were more like 120, you were paying royalty, and you know, like, somewhere in there, like, why not? Oh my God, that's really terrible. Like how have we come so far in 30 years, the way we think about things,

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 20:13

and, you know, I am grateful, you know, I don't hold anything against them. But I think that's where we were, you know, kind of fear fear based, you know, if you don't check your blood sugar, if you have a D on your agency, you're going to experience all these complications. And so I love like a lot of doctors and psychologists are trying to really focus on like, Let's do evidence based hope and motivate people based on these the other numbers of if you keep yourself in, you know, good range, or you exemplify or show these kinds of behaviors, you are going to live longer with, you know, and I can't pull the numbers out right now, but have a higher chance of not having any complications, as opposed to well, if you don't, you are going to have complications, right?

Scott Benner 21:00

Is it possible that aspirational talk doesn't work on people whose blood sugars are elevated all the time? Or have incredible stress about, like getting low? Or something like that? Is it is it feel like a bridge too far to even hope?

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 21:13

I think that's where you want to get that get them to, but obviously, in the beginning, you might need to start smaller. For example, let's focus on you know, the behaviors the process instead of the outcome. And if you're a parent working with a child or a teenager, you know, they catch them being good, you're praising the behavior of Oh, my gosh, you know, thank you for checking your blood sugar, and not asking what the number is, you know, thank you for you know, bolusing. I know you. And I really liked all your protests about the Pre-Bolus. And the timing of the Bolus is so crucial. And so praising them for or helping them around that piece, as opposed to what is your number now before we eat, what's your in the dish, the hyper focus on the numbers has to shift if you're trying to help somebody move away from that shame based thinking around your number and your agency, because that's where a lot because that's where you do need to focus on but at the same time, you need to take that piece away to help elevate a person's mood or distress.

Scott Benner 22:25

I don't think about the numbers at all anymore. I think about an atlas and my daughter has a Dexcom CGM. So I'm lucky to be able to see a graph, right, but I just think about, like stability and maintaining the stability. To me, the rest of it doesn't matter. carbs, you know, try to force the line up insulin tries to stop that. It's, it's kind of, I really, I simplify it in my head, just you know, you know, you see a blood sugar that's darting up, you stop it, just stop it, you know, and once it stopped, if you if you've over addressed it, then, you know, fix that without it. Going back up again. And learn from your next mistake, I think, you know, if you've overcorrected? Don't spend a lot of time hand wringing and saying to yourself, like, Oh, I've messed it up again, like, you know, like, just looking okay, well, look, this time I tried one one was too much, I'm going to try three quarters next time, I don't know, whatever, you know. And then you'll learn and build and learn and build. And before you know it, I just, I just saw a note today, in the I have a private Facebook group for this podcast, and a woman said, I came in, I was really desirous to just have success right away. And I almost just went right to the protests, she's like, but instead I just went back to the beginning of the podcast, and I started listening over, she said, she was like, 40 episodes in. And she's already has an incredible improvement in health, and her ability to manage blood sugar's and I said this to somebody privately the other day, I said, I know that the podcast has 400 episodes at this point. But the truth is, in my opinion, you go back and listen to this podcast straight through, you're gonna have a one C and the low sexist, and it's not going to be tough to get to. And that's because there are so many little things about diabetes, that if you expect someone to sit in a doctor's office, or in a, you know, or, and tell you about, it's not how it's going to happen. Like you have to hear it kind of slowly, you have to hear it as a building narrative. It takes a little time to take in the information. And after that, you know, you're on your way, like so I like that you don't blame your doctors, but I'm gonna blame them for you a little bit. You don't have to. We don't teach people how to manage their insulin. We just tell them they have diabetes, and that carbs makes their blood sugar go up and insulin makes their blood sugar go down. And then we're like good luck, and then they send them on their way. And then these little things that you're talking about I naturally pop up in life. And by the way, you don't just have diabetes, you also have a job or you go to school, you might be in a marriage that you're not happy with, you might be in a marriage you're really happy with, but there's a hole in your roof that you can't afford to fix, or any number of other obvious life things happen. While you're trying to figure this thing out, I've said over and over and over again, that I was able to come to these ideas, partially because I was a stay at home dad, and I didn't have to get up and go to work every day. You know, I too many people are in that situation where it's basically they throw a patch on their diabetes and hope it holds till the next time they're able to look at it.

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 25:37

Right? Yeah, I mean, there's just, it is a it is as they say, you know, the full time job that doesn't take a break. And, uh, you referenced that a lot. And I think it's upon all the other layers of life. It's exhausting. And I think one of the greatest gifts you can give yourself as a person with diabetes or a caregiver is to be kind, you know, use it don't don't wring your hands, let let the numbers be data for information for decision making in the future, but not a data point to say, Gosh, I really was terrible. I can't believe I didn't give myself enough insulin or GnuCash. Now I'm doing the diabetes roller coaster where I I was high, and I overcorrected. And I'm low cost sheet and then you get in your headspace app. So you know what I made a mistake. And that's okay. And I'm going to learn from this and move forward. As opposed to just ruminating in the number and the behavior that got you to that number.

Scott Benner 26:34

And I think Additionally, you have to have the foresight to realize that you can't make a mistake. If you don't know what you're doing. You don't mean like that's, that's an interesting concept, because you feels like you made a mistake. But if no one taught you, are you making a mistake? Like, you're gonna be like, how can I make a mistake about something I have no knowledge of whatsoever, the mistake is made in the entirety of how we do this, of how, from the moment you're diagnosed, until the moment someone lets you go, they tell you a lot of really important stuff. And not, I mean, you brought it up a second ago, and we kind of always just like, skip over it, but I have contact with a lot of people. The idea of Pre-Bolus thing, which is honestly the idea of understanding how insulin works, is not mentioned to most people when they leave with it's just, it's fat. It'd be like tell it would be like if I gave you a driver's license, it didn't tell you gas was flammable. You know, FYI, you know, right, right. You just got to the gas station, like it's leaking all over the place. No big deal. No one mentioned to me this was a problem. Like it just you need to understand how certain things work, so that you can be thoughtful about using them? Uh huh. I don't I see you're making me upset.

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 27:52

We know I thankfully, there has been such a huge shift in trend with, you know, the American diabetes Association has partnered with the American Psychological Association, APA, the APA, to recognize that there needs to be this focus on psychosocial care for people with diabetes, because the education piece that you are, you know, that you have done such a great job in broadcasting through your podcast is so crucial, combined with the psychosocial piece. And so I am grateful that there's been a big shift and care for not only endocrinologist, but psychologists focusing in on that the emotional piece of what it's like that, you know, it's it's exhausting is the understatement,

Scott Benner 28:41

right? It just it's, it's the tools, you have to have the right tools, where you can't you just can't You can't build your box if you don't have a hammer. And that's that. And it's not, it's not that much more difficult. And like you're saying the other side of it is, is that while you feel like you're constantly failing, and failing and failing, and you're not just failing, but your health is deteriorating, and you're starting to feel worse, and worse yet, you don't notice it after a while. All these things are just, you know, they feel insurmountable. And I think possibly, then I'm not just saying this, because you're here, the only way most people are going to be able to climb out of this hole is with third party help somebody who can break it down for them and show it to them piece by piece, and then give them direction about how to how to manage

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 29:30

it. Well. Yes, I mean, I think there is you do first to be you know, aware of the signs and symptoms and actually, as I was preparing to come speak with you today, I found this website, it's called diabetes distressed.org. And then you can actually take a survey to kind of assess your degree of distress and it highlights you know, don't worry if your numbers are higher, you know, join to really prevent It's no, there's no shame around having distress. But to first like, let's just try and go be aware of where you are in your level of distress and then it gives you some options of what what do you need? You need to talk with your healthcare provider? Do you need to seek additional help with a mental health provider? Do you need to become more clear with your family of what you need? Do you need help and problem solving? Or do you need just more validation from your family? Or your partner who whoever's you know, in your, your immediate family support system? I think understanding where you are is the first step and then kind of figuring out how can you help yourself through that process and being kind and compassionate to yourself is also really key.

Scott Benner 30:49

I think we should be deputizing sharpest diabetes Sherpas, I've just come up with this idea while you're talking. Because, because you just said stuff that I could imagine a new blockade for every time we'll go to your doctor, what if my doctor sucks? You know, what if my doctor thinks a 7.8, a one sees great, like the and I don't think that or you know, and it's easy to to say to somebody, like don't just see the number. But, but everybody's not great in a panic situation. You don't mean like, there's there's certain people who, you know, there could be bombs going off around them, and they can stay focused on what they're doing. And there are certain people who hear the bombs and very reasonably jump on the ground and cover their head. So when, when ever when you can't count on everybody being so resilient in that moment, you know, like, they need somebody to take their hand and go, Hey, look, you're in over your head, no big deal. Like it's that old story, right? Like guys down in the hole. His buddy walks by yells up, Hey, Bill, can you give me a hand, I'm stuck down in this hole, and Bill jumps down in the hole with them. And the guy goes, What are you doing? Like now we're both stuck down here and bogus. Now don't worry, I've been down here before I know the way out. Like you need somebody who who can lead you out. And, and I think that there's too many, there are too many variables. And, and you're also counting on people to recognize which bucket they fit in. And then they have to go to the right person, like you just need somebody to stop, listen to your story and say, Okay, here's what you need my opinion. I'm going to try to get you to it. And let me see if I can't lead you forward. If you've just given me a job for after the time when the podcast is over, I'm going to start diabetes chirping. And I think this is I think this is it, because you don't need any special skills. Just to know the path somebody else doesn't know and, and is too confused to find their way on at the at the moment in their life that they find themselves in that situation.

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 32:53

Right. I mean, yes, oftentimes, yes, someone coming alongside them, helping them through the process and just validation that, you know, I understand that you are in such a challenging and difficult spot and also feeling like they're not alone. I think that's, you know, with, particularly with type one, it's, you can feel very isolated, that no one really understands the challenges, the nuances, the you know, every thought, every minute, you there's a different thought probably about it about your diabetes management. I agree. And that can feel so isolating. And so I think reaching out for help just for that, to know that you're not alone is also a really crucial step.

Scott Benner 33:44

Yeah. No, I agree. Having some sort of community. I have to be honest, that I've been shocked over the last number of years when people write to me privately to tell me that this podcast is their community. And even though they don't have a back and forth, it's not a it's not a two way conversation. It's still everything they needed, was just knowing someone else existed in being able to listen to them.

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 34:05

Yes, and not feeling like they're alone in the process. And I think that's, that's, you know, one of the benefits of technology and your and your podcast and all the many resources that you can access online.

Scott Benner 34:20

Yeah, no kidding. Okay, so Eric is so so somebody can come to this burnout phase, show up, find a therapist that understands diabetes, and hopefully find their way through it. Will the therapist help them with management to or No,

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 34:34

no, and that's, that's a great clarification. You know, even though I have type one, you know, and sometimes you're like, I'm an expert, not always with my own management. I'm not the expert of everyone else's own personnel management. And so I oftentimes will consult and collaborate with their health provider with their doctor with their end with their see Do E, and but I would not make decisions or suggestions around their insulin management or carb ratios. I would come alongside them and help them maybe figure out a behavior plan with either the caregiver or depending on the age of the person with diabetes, and help support them in that way and kind of finding what what are the roadblocks to implementing that behavior plan. And also, just as we already talked about just kind of the validation of, of the challenges of living with diabetes.

Scott Benner 35:38

You've never you've never leaned over the table seen the graph and been like you consider just up in your meal ratio a little bit?

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 35:46

No, that would definitely be out of my scope of competence and practice. So yes, that would not be appropriate.

Scott Benner 35:54

Well, good luck as you your principal person, you Erica. So So let's let this is something I'd like to dig into this next thing that I'm constantly enamored by, which is I believe that when you're diagnosed with an illness, that is not the it's not curable, that you go through the processes of grief. Am I right about that? G voc hypo pan has no visible needle, and it's the first premixed autoinjector of glucagon for very low blood sugar and adults and kids with diabetes ages two and above. Not only is G voc hypo pen simple to administer, but it's simple to learn more about. All you have to do is go to G voc glucagon.com. Forward slash juicebox. G voc shouldn't be used in patients with insulin Noma or pheochromocytoma. Visit je Vogue glucagon.com/risk. Are you ready to ditch the daily injections or send your pump packing? If you are, it's time to try Omni pod, the tubeless wireless continuous insulin management system. Here's all you have to do. Go to my Omni pod.com forward slash juice box scroll down a little bit and decide do you want to check your eligibility for a free trial or check your insurance coverage to see if you're covered. Maybe you're already sold and you just want an on the pod just click on my coverage, I want to check my coverage, then fill out a tiny bit of information and you're on your way. Now if you're just looking for the free, no obligation trial to be sent to you check my eligibility for a free trial, fill out your information. And that Omni pod will show up right at your house so you can give it a whirl. It's just a demo pod Don't worry, you put it on your where you see what's up. And the questions are super easy. You know, my name my date of birth? Do I have type one or type two or another type of diabetes? And how do I currently manage it's very simple only takes a moment to get that free, no obligation demo or to get started with the Omni pod at my Omni pod.com forward slash juicebox you want to learn more about touched by type one check them out on Facebook or Instagram or at touched by type one.org So wonderful organization helping people living with type one diabetes touched by type one.org My Omni pod.com forward slash juicebox G voc glucagon.com forward slash juice box support the sponsors support the show

you go through the processes of grief. Am I right about that?

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 38:46

Absolutely. And I I probably see the majority of my clients and families are mostly the newly diagnosed who are dealing kind of with the shock with the grief kind of the the exploration of what what does this really mean for our family? It is it's a you know it's a community that you don't really want to be a member of but you're trying to figure out what how is this going to affect our daily lives and you know, some people like for my in my family for instance I actually also have a younger brother with type one. Coincidentally which and I have an older sister who does not and no one else in my family had we have no history of type one diabetes. So I had kind of that built in community with my brother which was unique, but a lot of family so you know we're gonna we're gonna fight through this. We're not going to let this affect us at all. You can do all the things you want to do. We both played volleyball he actually was this is my little brag spot. He was an Olympic gold medalist playing volleyball in Beijing. And so I just like to say that that you can do Do whatever you want to accomplish to a set, you know, within the means of you managing it. So, there are some families on that kind of end of the spectrum. And then there are other families who are really struggle and i It's understandable who, you know, how do we, how do I let my child go to school? And how do I trust other people to manage this, this is you know, thinking from a younger, aged person with diabetes, to a teenager who wants to go out or wants to drive. And now is kind of Tet tasked with well, you have to have your blood sugar in a certain range before you get to go out with your friends or drive your car. So it is such a huge shifts, and obviously different with different layers and different complications based on the age. Yeah, but to answer your original question, yes, there is a huge sense of grief and loss around and sometimes it's just ambiguous loss. Like we don't we're not really sure what we're all at all that we don't you don't really know, you know, everything. Sure, initially. And so there's this sense of like, ambiguous loss and grief. Yeah.

Scott Benner 41:14

Is denial always first? Or not necessarily, I guess the the stage. By the way. I've also heard from some psychologists who say that they don't call it the Stages of Grief anymore. Like there's other ways to think about it. There's some thought processes were there are seven stages, five stages, two stages. So keeping in mind, there are different ways to think about it. But I can tell you like right off the bat, I know that I, I personally experienced denial, and it popped up around a honeymooning situation, yes, right. As soon as you didn't need insulin as much, or, you know, there was this, this may be 24 hours where my daughter just didn't seem to need insulin at all. I'm sure she still did. But I was such a neophyte at the time, less seemed like none. And I got I got caught up in it to the point where I called my friend who's my my kids, pediatrician, and I was I was coherent enough to say to him, I actually said, Hey, I'm going to say something, after I say, tell me I'm wrong and hang up the phone. You know, I said, But you know, most people can't talk to their kids doctors that way. But I happen to happens to be a very good friend of mine. And so I said, I don't think Arden has diabetes, she hasn't used that much insulin. And he said, No, Scott Arden definitely has type one diabetes, this could happen, you know, in the beginning, and he described honeymooning to me back then, but I was in such a state. I didn't even hear what he was saying. I just heard him say, Stop hoping she doesn't have it, you know. And that was pretty early on in the first six months or so. And I wasn't, I wasn't out of my mind enough to just be thinking it all the time. But the minute that something concrete happened that opened up the possibility I ran through that door, right away. Everybody goes through that. Do you think denial?

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 43:07

Oh, I, I would probably say even I can't say you know, give a fact on that. But I would say a lot of people probably would kind of win in your, you're in shock, your denial, you're kind of trying to figure out what is this mean? Then there's this honeymoon period, which can last, you know, different lengths of time for different people. I think along with the denial, a lot of parents and my own included feel guilt, or would rather say Can I Can I have this instead of my children? Or Did I do anything to cause this? And so those are all really challenging feelings and thoughts to have. And so often, instead of kind of either expressing those or feeling those, and moving through them there is there can be that denial. But that's all part of yeah, that the stages of grief and shock and like you said it, the Stages of Grief are not linear. They are cyclical. And so you can experience any of those stages at any point in time.

Scott Benner 44:09

We're all like, Yeah, I'll tell you that. I've seen. I've talked to people who when they get to anger, they go a lot of different ways. It's, you hear like, you know, I don't know how God could let this happen. Like that's, that's one that I that I hear pretty frequently. Some people go take their anger and drag it right into domination. Like we're going to support somebody who's going to cure this, we're going to find some, you know, a doctor who's working on something that you've never heard of before, like that aggregates or I'm going to keep my kids blood sugar at 84 constantly and it's never going to move and they direct. I've seen them direct their anger at that as well. That could be X Last thing, though no.

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 45:01

Oh, for sure. And the anger could also go to the, you know, the burnout. I'm so over this, I'm so angry. I'm I just don't want to think about it. And so I'm going to just ignore it.

Scott Benner 45:17

Okay, so can the anger, like, could jump right to that we're just I'm so mad at this, I'm going to pretend doesn't exist, you could also be driving so hard to make it perfect that you end up burning yourself out through that.

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 45:31

Yeah, that is a that is an excellent point. Yeah, you can you can experience burnout from the other, like, I'm gonna just hyper focus on these numbers, I'm going to keep it in this perfect range, you know, from 80 to 120. And keep it like, try to be a, quote, normal person. And that, as we know, is is fairly impossible to do on a 24 hour, you know, 24/7 basis. And so you certainly can burn yourself out, particularly if you're the caregiver in that role. Because then that that often leads to you if you're going to be perfect, that often leads to feelings of guilt and shame. You know, like, how did I let it get to be 121? Yeah. And so it is, it can be a very messy cycle of trying to live in this, if anger is driving that trying to live in this perfect range. And that's where I would encourage, you know, the self compassion piece to come in.

Scott Benner 46:26

So do you. Can you, I should have said, can you explain the bargaining step to me? Because it's, that's the one that doesn't make sense with how my brain works. Like, I like I saw it happen. I feel like I feel like bargaining covers, this is my fault, because there are no issues in my family, like, by people, or they're the people who feel like if they would have gotten to a doctor sooner, there could have been something they could have done about it. You know, or it's my fault. I didn't see something like that. Is that all kind of falls under the bargaining portion?

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 47:05

Yes. And I think it's, it can happen fairly. It's common, particularly, you know, with parents, like I said, you know, bargaining, like, why can I have this instead of my child? And I think it happens, because we often really don't know, the initial trigger, right to your pancreas not working the way it's supposed to. I think if we had a clear, you know, trigger, and a clear explanation as to why the bargaining and the the either the guilt wouldn't happen as much, I'm sure it would happen to certain degree because you still don't want your child living with a chronic illness. But that the confusion around the the actual diagnosis of type one diabetes is still very much you know, they are. And so we want it we always want we want to know why, like, how did something how why did this happen? How could I have prevented it? Could I have done anything differently? Did I you know, do we use the wrong detergent? I mean, I hear all sorts of things. Maybe it was because that my child broke their arm and their immune system was in shock. Or maybe it was because my child had the flu. You know, we, we want to always figure out the why. And we don't really know why with this.

Scott Benner 48:23

It's funny, I don't care about the why, like, even when I talk about blood sugars with people, I tell them, one of the biggest mistakes you make is staring at a high blood sugar wondering how it happened. Like I don't like I don't care how it happened, just use some more insulin and get it down. So the bargaining the bargaining part didn't like, to me bargaining is that it's your brain's last vestige right? To keep it from feeling sad. Right? You're trying to you're trying to stop yourself from getting to the depression part to the, to the grief part. And so you keep trying to figure out a way where this doesn't have to feel sad, and there's no, I don't, there's no way not to feel sad about getting diabetes, like it just it's not a great thing to find out that one part of your body stopped working, it isn't going to start working again. Sucks, you know, but I get why it happens. But I wonder if people listening, can't hear what we're talking about right now. And then go back to any number of other episodes and other people's stories that you hear and realize that all of their stories are just some version of the steps that you feel after something like this happens these stages. Yes, you know what I mean?

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 49:38

Yes. And and then you know, getting to some people say, you know, the last stage of of grief is acceptance, but as I, you know, want to highlight, you can you can accept the diagnosis for a period of time, but it's okay to go back to periods of feeling sad, you know, I love to tell the story. I I had a stint I worked at the JDRF and so Francisco many, many years ago, and there were a lot of type ones on staff there. And there was one particular woman who had had it for over 50 years in great health. And she, I think it was either once a month or a couple of times a year, she would take I hate diabetes Day, she would take if she would take the day off, she would lay in bed, she would, she would feel all the feelings, she would feel sad, angry, and then move on. And so she kind of had this planned out to be like, you know, what, I'm living with it, I'm living successfully with it, she had a very robust life. But she still had these moments and created these moments for herself to feel sad and angry about it. And that was, that was her way of kind of coping. And that's okay, so even she lived in kind of the most, the majority of her life was a life of acceptance and thriving, but it's okay to come back to feel like cash. You know, we all have different seasons of life. And there are going to be more challenging ones with with your diabetes, particularly, as you're growing and going through different seasons in hormones and different life stages and different stressors. So it's, it's okay, yes, to have those different emotions around it. So just

Scott Benner 51:17

because you got through the, the, the depression and grief state, and you got to acceptance, and you started thinking, hey, you know what, it turns out, I figured out how to use my insulin and this sucks, but it's, you know, you know, everybody's like, who's way better than this other thing that could have happened to me or, you know, whatever. So I'm feeling good about this. Now I'm, I feel like I'm in a little more control of what's going on. And you start sort of just turning the corner, it doesn't mean that you can't remember one day that this sucks, if you don't just get the dislike, it's not the so it's for people's understanding, like the five stages of grief, I think, is like an older idea. There's a seven stages of grief, that, that breaks things down a little differently, and is way more hopeful at the end, where you kind of, you start putting things back together, again, you're working through them, you accept what's going on, and you actually end up feeling very hopeful. And just because you feel hopeful today, doesn't mean that something won't that you know that your pump won't fail, while you're on, you know, a roller coaster at Six Flags, and you won't be like, Oh, this is depressing. It's ruined my whole day like you can you're gonna bounce in and out of these things as you go. And not just the diabetes, by the way, life in general, I don't know if people realize that we're all very basic, like, organisms, right? Like, we just we sort of do the same things over and over again. And when we reapply them to different ideas, somehow we're like, oh, diabetes is sad. Well, everything is sad at some point, you know, like, I get depressed about things like everyone else has, the bigger issue ends up being for people who hit that depression, pothole. And for real, physiological reasons, can't actually get out of it ever. Like everybody gets depressed sometimes, but most people are able to get through it, the people who aren't there now, now they've now found a new another new issue that they need to deal with.

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 53:14

Yes, yes. And I think that's, it's important to note that, you know, when we're talking about diabetes distress, it's, you might experience a certain level of, of distress at certain points throughout your, you know, career with with diabetes, and that's okay. I think the, the important part is to be aware of when you feel like as you just were describing, you know, that when did stress becomes, you can, you can have diabetes, of stress and struggle with the elements of living with diabetes and not be depressed, because maybe you're functioning in other areas of your life or your job, your, your family life, your friendships. If you're an athlete, you know, it's, it can be different. But when it becomes when diabetes distress is prolonged, and you aren't able to either recognize the symptoms or reach out for help, or have community around you, that can you know, it can transition into, you know, a full blown depression diagnosis. And I think that's, that's what we're trying to prevent. Yeah, you know, before it kind of impacts and impairs all of your levels of functioning,

Scott Benner 54:22

are there just some people who are predisposed and eventually they're going to have a turn in their life that is so impactful, that they're going to become depressed, like like that. It's always going to happen.

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 54:36

That's that's a great question. I feel like could be almost another another episode. I feel like Pete I see you're asking like are people are people predisposed to having depressed thoughts or experiencing depression?

Scott Benner 54:51

The same idea with diabetes, like if you have the markers, the genetic markers for type one diabetes, then your likelihood of getting it goes up and So, if this happens, and that happens, and everything just kind of goes wrong for you, boom, you have type one diabetes, there are other people who have those markers, who never end up with type one. And so I'm assuming there are people who have markers for depression that they're unaware of. And then if they have life, circumstances that pushed them in that direction, that they are more likely to get caught in a real depression than other people are, because I've had some fairly terrible things happen to me in my life. But I've never had long bouts of depression. And there are other people who have had things happen to them that you know, are equal to mine, or less or more who gets stuck in it for ever. And so my assumption is that, I don't know. Do you understand what my assumption

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 55:44

is? Yes, yeah. Yeah. Are you are you kind of more prone to either depressed thinking or experiencing depression? Because of certain genetic marker? Yeah, I would say yes, that that is certainly does exist. But there's also the other components of life like the, your, your resiliency, you the people around you, the support that you have, I think is really crucial. If you are experiencing a, you know, a triggering event that might lead to depressed thinking or symptoms or error or clinical depression. The the capacity for you to reach out for help. Now, are those all due to genetic markers? Maybe are those due to the fact that maybe your the community around you can support you or not? There are a lot of different I would say factors around that. But yeah, I'd say it's a both it's Yes. Both? And to answer your question,

Scott Benner 56:45

do you think that peeps are people who maybe know in the past that they've had trouble or gotten stuck for longer times than maybe feels? What they see normal around them? If something like this happens to them? Should they be running right to a therapist? Should they be should they literally like, leave the hospital and go and call the therapist and be like, hey, look, my kid was just diagnosed with type one diabetes, I got a feeling this isn't gonna go well, for me, like, let's start now. Because I've interviewed people who have, like, I just did an interview the other day, that it'll be out in a little bit where, you know, this, this woman describes an incredibly happy life. And then at one point, she felt suicidal and said, she had never felt that way ever. And it was after a diagnosis for a child. And then, you know, just as you described, had had a spouse with her, that was able to, you know, kind of keep her focused, as this thing had ahold of her. And it took a very long time for her to get through it. But she luckily had somebody with her in that moment. You know, she could have been by herself, I just feel like, you know, what, if she was a single parent, or didn't have a lot of family around her, like, how do you? How do you make that decision to get help when getting help? Seems like another failure?

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 58:05

Right, right, or just another problem. Another problem, another thing to do, and maybe if you are in, you know, an extreme level, experiencing extreme levels of depression, you know, it's hard to motivate to do anything. And I think if, if we're talking about this, within the scope of diabetes, I mean, hopefully, because there has been such a shift, and a trend in, in our medical health providers, or healthcare providers to be more aware of the psychosocial symptoms for not only the person with diabetes, but also for the caregivers, that they would be assessing, you know, both both parties, their level of their psychosocial care, their mental health. And so, my, my hope would be that, that would be the starting point, you know, whether you're, you're coming in for your, your checkup, or you're bringing your child in for a checkup that they would be asking those questions. And if not, that you would be able to tell them, you know, how you're doing. And your question is, what if it becomes to a place where you feel like you can't reach out for help? I think that's where, if maybe reaching out for a mental health support is too much, maybe exploring insights like your like your podcast, you know, realizing that I think depression likes to tell the person that they are alone in that, and it becomes isolating and it feels really scary to be in that state of mind. And so recognizing that you're not alone in that and if it's just means listening to your podcast, if it means going on a different website. JDRF just had their their summit and there's a lot of great resources on their website from their summit this over the summer,

Scott Benner 59:56

or what was wrong with the idea of listening to the podcast, what are you doing, driving people away? What are you doing? I'm just kidding. Wherever you can find help, I'm happy for you to find it. Well, okay, so I know we're up on an hour. Do you have a little time beyond the hour? If I drag you past it or you have a heart out?

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 1:00:13

I have. I have a little bit extra time. Yes. Okay. So

Scott Benner 1:00:16

I have one more question. That's the real simple thing real quick. Is it true? I was told this, that my daughter's diagnosis that the that in America, one in two marriages end in divorce, but when you have a critically or chronically ill child, excuse me, it goes to two and three?

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 1:00:37

Well, I don't I don't, I can't back that up. But

Scott Benner 1:00:40

is it more likely you're gonna get divorced if your kid gets sick?

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 1:00:44

Gosh, I hope not. No, but I think like any other major stressor, be it financial or, you know, job, job insecurity. That's chronic, you know, any other chronic stressor in a marriage is, is a challenge. But I think the the important piece is, and I think you mentioned this in one of your podcasts that, you know, if one parent is the sole caregiver for the person, for the child with diabetes, that's, that's there's going to lead to burnout and maybe some feelings of resentment, unless that's already established. And you've communicated that. And that's the way you all want it to be, which would be hard to believe it. That's it. But if that's how your family setup works, then that's great. But I think the communication piece is so key and understanding without a sum without assuming, okay, well, you know, mom's at home, so she's going to take care of Bobby and or vice versa, like in your case. And so I think if there's the communication around that, that would help prevent issues of resentment.

Scott Benner 1:02:02

Oh, it's really easy to be like, Look, I'm doing everything and you're doing nothing. And, you know, because you because especially in the beginning, if you don't know what you're doing, it's already mind numbing. And then you start having that feeling like you're killing the person, because you can't figure out how to use the insulin. That's an added thing, then you feel like you're alone, and you're by yourself, and no one's helping you. And then when your spouse acts like, oh, that's your job. You're like, oh, wait a second. You know, like, I would love help. But it's also not reasonable, like my wife and I came to the conclusion that it needed to be one of us. Because as we tried to pass it back and forth, we would just we found it impossible because we found ourselves having to, like, you know, recount everything that had happened for like the nine hours prior, like, Okay, so for breakfast, you know, it's six o'clock at night, and you're telling someone who just got home from work, or breakfast this happened or use this much. And it happened with MPW and then at lunch, and then this and then you feel like you have to you feel like your nurse passing off to another nurse. Right? And so one day, we were like, Alright, look, I'm gonna take care of it, we won't pass it back and forth, because this wasn't working for us. And so I don't feel any, like, bad feelings around the fact that it's, it's more me than it is her. But how did just happen that way? Had she just like, buried her head or like, you know, turned her back on me and started kicking the ground. Like, she found something interesting. While I was doing diabetes, I would have been angry, like, quick, right, you know,

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 1:03:33

right. So yeah, you guys had that kind of predetermined role and responsibility set. And I think that's, that's key, you know, a lot of a lot of arguments or misunderstandings in just in marriages in general is without, you know, assuming things, feeling like someone's someone has responsibly do something when maybe it's a joint responsibility. So I think that's, that's great that you guys had that opportunity to have that conversation. Yeah. And agreement. All right.

Scott Benner 1:04:03

I'm gonna ask you to generalize, then you're gonna tell me you're not going to, but it's not going to stop me from asking, Okay, I've realized you're too professional and you're on the ball. By the way, you must be really good at what you do. Because I talk in big word pictures. And you remember my question and come back to it afterwards, which I find incredibly impressive. I don't hear you making things so well done. But look at me, I'm just like, I'm so impressed by that. Well, thank God no, seriously. But here's my here's my statement that I'm going to ask you to agree with or are telling me that I'm wrong. Boys are boys and then they grow up and become men and then they marry people and then they're not as much help as the women just say it right? Like, like women are more generally speaking, focused and familial, and guys are more like I made money already. Let me get to my PlayStation. Like that kind of is that true? I know there are some men who aren't I'm obviously one of those men. and who isn't like that? But for the most part, if we were just going to generalize, women are screwed, right? Go ahead, say,

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 1:05:08

Well, I'm curious, I'm curious as to where where you're going with this,

Scott Benner 1:05:12

I grew up in a blue collar world where men did not get involved in family. And then it all seems to be like this, you know, quiet agreement that people come to in their marriages, I do this, he does that he does this, I do that blah, blah, blah, and it all kind of works out. And the resentment is quiet takes decades to build. But then when you bring in the diabetes, real quick, everything gets jacked up. And now suddenly, he's not just ignoring the fact that the Christmas decorations need to go back in the basement. He's ignoring the fact that your kids blood sugar's 250. And now, and now what ends up happening is this goes from a thing that I find irritating because the house is a little bit of a mess, or we haven't fixed the hole in the roof or something like that, too. We're killing our kid and you don't seem to care. And then it has been my, my experience. And what I've witnessed from other people, is that women appear to have a genetic component to them that once they give birth to a child, they care very much about that child, and a lot less about everybody else who is not that child. So now you suddenly went from being like my boyfriend, who became my husband to becoming this guy who doesn't care about this to 50 blood sugar, and now you're a danger. And am I wrong about all that? Like, that's just how I see people?

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 1:06:35

Yeah, well, I think, you know, I, you're right, I'm not gonna generalize, because

Scott Benner 1:06:40

you wouldn't use your professional.

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 1:06:45

Eye? Because, you know, look, look at you Case in point, I think there are families who create different structures for that within themselves, I think the issues that you are, like the example that you just gave, occurs, when there's not, there's no communication, and that now they've gotten, they've just kind of, you know, the partners have been set in their ways. And for better, for worse, and then when a when a major stressor occurs, such as a diagnosis, the, the rhythms and routines can become, obviously troubling, but then then it's exactly exacerbated because now we're talking about our child who it's it feels life or death, you know, to manage their diabetes care. Yeah. And so if there's already this built in resentment that I'm doing, I'm doing X, but you're doing y. But now you're not helping me with my child with our child. That creates, obviously, a major conflict. And so I would, I would encourage people to, you know, what, what you have modeled, and just explained within your family system, every family system is different. And while you know, there, there might be stereotypes of what the male or female or different partners do. It doesn't really matter when it comes down to your child who's living with diabetes, to get really clear with who was doing what, and what does that look like on a daily basis? Because if it's not clearly communicated and understood, then that resentment and that burnout is going to happen for the caregiver. And you know, who knows what's happening for the child with the diabetes?

Scott Benner 1:08:35

Allow me now to argue the other side of it? Because really, did I believe what I said? Or was I just painting a picture, okay, and now, so here's the next side of it, right? You can get into a situation where, hey, you one person are in charge of the kids, you make decisions like this, I'm not involved, I haven't been involved in two years, three years, four years, five years, I feel out of the loop. You seem to be doing such a good job with the diabetes, this is a scary thing. I don't know anything about it. I'm very afraid to mess it up. So I think that there can be a time where one of the spouses looks disengaged, but is really just frightened out of their mind doesn't have the extra problem of being the person with the kid. So they get the walk away from it, whereas you are frightened out of your mind. But you're stuck there making the decision. So you figure something out, tried, it doesn't work, try something else, this works. Now you're going through trial and error on your side, the other person's not going through that. And because of that, they can feel more like hey, maybe I should stay out of this. I think there are plenty of people who heard me say the first thing that I said and thought, yeah, that's right, my husband or wife is is an evil and they don't help me with this and blah, blah, blah. But I also think that that person could have heard it and thought I just don't want to mess this up. And it seems really important and I don't know what I'm doing. I think that there's a misunderstanding, almost constantly between married people, but I think we mischaracterize each other almost constantly. Do you think that's true? You talk to married people? Do people not really understand each other?

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 1:10:13

Well, I think, not not consistently, but I think there are moments or events, or going back to, you know, just any stressor that might challenge our, our understanding of one another of what the, you know, relationship looks like. I think, you know, I'd be curious and in the, you know, I have seen couples who are, you know, we, I'm working with it with a child with diabetes, but also the couple, who are are struggling with that dynamic of, well, you know, she takes care of the house and I and I do the diabetes, or vice versa, or, you know, whatever, whatever role is defined for each person. But then there's that the fear of not knowing or maybe the other person is feeling like the partners passive in the in the children's care, diabetes care. So I think it all goes back to what, what is everyone feeling in the moment? Let's communicate around that? I mean, I'm curious if you do have check in times with your wife like, does she want to, to be more a part of the

Scott Benner 1:11:23

care or a better note with her money making money, Erica, She better not lift her head up, I need her working. Understand. She's not allowed to look up, she's allowed to eat, use the bathroom twice and work. That's it. That's her job. No, we, when, when life allows, we bumped into each other and fill each other in. Right. And that really ends up being how it goes, I would love to tell you that I have a specific time for but that's not reasonable. You know, sometimes it's before bed, which by the way completely kills the idea of having sex and you're like, Oh, the kids are having trouble with school and blah, blah, and you're just like, I'm gonna go to bed now. That we're, you know, like, we'll stop, I have to be honest, because of COVID. We're around each other more often, we just had a conversation before I jumped on with you about something that would not have happened before. And I'm going to tell you, from my experience, these little like pitstops are super important. Because once they get to build up, your conversations turn into this mishmash of like you blurting out a bunch of stuff you meant to say, her trying to respond, she blurting out a bunch of stuff she meant to say you try and respond, I've never seen one of those conversations go well in my life. But you know, like you have to every once in a while stop and say, Hey, did you see that this happened? Or that, you know, college said that they're gonna go back. But this that doesn't seem right. Maybe we should figure something else out. Just keep people thinking about things over time, like they're, to me, it's just a constant conversation. Yes. And it's doesn't always go great. It's just the best you can do. The problem with managing a life is that you're trying to live one at the same time. Yes, there's two competing things happening and every second of your day.

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 1:13:05

Yes, and I think sometimes for the caregiver, you know, the caregiver just might need some validation to I think it's important, just like we're asking, I would ask the person with diabetes, to ask for what they need, do they need some more problem solving? Or do they need some validation? I mean, those aren't the only two things you could be asking for. But those are kind of the main points. And just like, you know, apply those same ideas to the caregiver, does the caregiver need some more problem solving around how to manage your child's diabetes? Or are they just wanting some validation of like, wow, it must be really hard to really monitor, you know, Bobby's blood sugars, while also trying to do all the things you want to do for your own life. That must be really, really challenging. And thank you so much for doing that. I mean, I think, like, basic validation, and gratitude goes a long way. But to be to ask for what you need as a caregiver, and also for the person with diabetes if you're able,

Scott Benner 1:14:04

and this goes for being married in general, right, like, because I think that I think that overall, people think there's two ways that marriages end either you just get sick of each other, and you go your separate ways, or you give up and die. And that's not to shouldn't be the two basically conceived endings of how marriage go. You know, and I think there's a way to realize that there, you're shooting for a long time, that there are going to be good days and bad days, good weeks and bad weeks, good months and bad months, good years and bad years. Like I once told my wife when we were first married, she's like, what's your expectation for all this? I said, well, listen, if we stay married our whole life, it'll end up being maybe about 40 years if we're lucky. I think if we have you know, 10 really great years and 10 Okay, years and five years that sucked and five years that weren't too bad. that'll probably be pretty good. You know, like, like, I mean, I think that a striving for perfection constantly. Is A bit of a fool's errand, and it really just leaves you more let down than fulfilled. I think there's, you know what I mean? Like, everything can't be perfect all the time.

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 1:15:11

That's exactly and that leads to the thinking of, you know, I'm I'm not a good enough, you know, parent, I'm not a good enough caregiver, I'm not a good enough partner spouse. And so yes, the the, the validation, the gratitude and the self compassion are, are key to kind of get through the long haul of of diabetes when the in the family system for sure,

Scott Benner 1:15:33

right. Yeah, yeah, once you've heard my stories, 800,000 times, there's got to be something else that makes you go, I'd still be okay, waking up tomorrow if he was here. And like, you know, and I think what you just said is really important is that we're all just, I mean, listen, I can be completely honest, I need validation, just like everybody else does. I know, I'm doing a good job. But if the people I'm working so hard for don't appear to care, then what's the point of it? You know what I mean? And they can you can feel like that at some point, like, nobody seems to care. And I get that, you know, nobody's gonna run around telling you, I really appreciate my laundry being clean. You know, and I'm not looking for that. I'm not looking for someone to come up to me every five minutes. But there's a moment where, you know, Arden has Chinese food going into a donut and I don't let her blood sugar go over 110 where it'd be cool. If someone would look over and be like, Damn, you're good at that. And I'm like, Yeah, I'll

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 1:16:29

say that. I'll say that. That's really impressive. Eric,

Scott Benner 1:16:31

I'll put your NYC right in the fives. No trouble you come over here. I really appreciate you doing this. i This conversation was everything I hoped it would be. And I'm hoping you might decide to come back on more than once because I think there's a lot more to talk about. This was great.

Erika Forsyth, MFT, LMFT 1:16:49

Oh, wonderful. I would love to thank you. I really I really enjoyed it as well.

Scott Benner 1:16:57

A huge thank you to one of today's sponsors, G voc glucagon, find out more about Chivo Capo pen at G Vogue glucagon.com Ford slash juicebox. you spell that GVOKEGL You see ag o n.com. Forward slash juicebox. Don't forget, you can get your free no obligation demo of the Omni pod tubeless insulin pump at my Omni pod.com forward slash juice box and learn more about touched by type one at touched by type one.org or on their Facebook, or Instagram pages.

If you're listening in a podcast app, please press subscribe. And if the show has been valuable to you, please share it with someone else. Have a great day. I'll be back very soon with another episode of The Juicebox Podcast. You can learn more about Erica at Erica forsythe.com erikforsyth.com.

A huge thank you to one of today's sponsors better help, you can get 10% off your first month of therapy with my link better help.com forward slash juice box that's better. H e l p.com. Forward slash juice box. If you've been thinking about speaking with someone, this is a great way to do it on your terms. betterhelp.com forward slash juicebox thank you so much for listening. I'll be back very soon with another episode of The Juicebox Podcast.

If you have questions looking for support or just community, check out Juicebox Podcast type one diabetes on Facebook. It's a private group with 40,000 members, somebody in there right now actually, there's always somebody there. And they may just have the answer to the question you're looking for. Or maybe they're going to be your new friend or just the person you find amusing from the distance through the internet Juicebox Podcast type one diabetes on Facebook

Please support the sponsors

The Juicebox Podcast is a free show, but if you'd like to support the podcast directly, you can make a gift here. Recent donations were used to pay for podcast hosting fees. Thank you to all who have sent 5, 10 and 20 dollars!